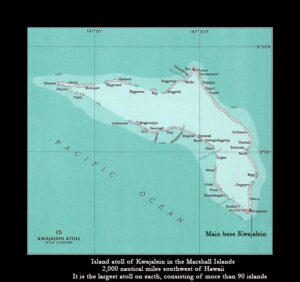

My father Arthur Hartung was a Chief Petty Officer in the US Navy Seabees—Construction Battalion. In the aftermath of WWII and the initiation of the US Marshall Plan in the South Pacific, he was sent to the island atoll of Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands located in Micronesia some 2,000 nautical miles southwest of Hawaii.

Kwajalein is the largest atoll on earth, consisting of more than 90 islands in its living chain necklace.

There my father felt perfectly at home. His avocation was a fisherman, and in his youth, he was an avid hunter. As a kid I remember many days fishing, lobstering and scalloping with him. On many long cold nights we would cover miles of upland ledges in Flanders, Connecticut woods. We hunted raccoon until dawn with his brace of hounds.

As a young husband he settled with his dear wife Phyllis and family along the banks of the Niantic River. It’s one of the richest estuaries that opens onto Long Island Sound. And it was not far from the family homestead of Soundview.

Now with his new assignment he was leaving the familiar environs of home for the unknown but alluring call of distant islands.

My father arrives in Kwajalein

Arriving in Kwajalein, the largest island in the chain, he commanded a construction group consisting of enlisted sailors. Additionally there were many more indigenous islanders referred to as Natives.

The US Marines who oversaw security in the islands looked upon the natives with some uneasiness and suspicion. In fact before the Americans took over the islands, the Japanese had inhabited them for some 30 years. Consequently, the natives spoke fluent Japanese as well as their own Malayo-Polynesian language. Because of this, the natives were not allowed to stay on the main island at night. Instead they were required to go each day at sundown to their homes on a nearby island and return each morning to work.

This indignity was not new to the island natives, as they suffered a long history of foreign domination. Their story has been traced back to before the birth of Christ.

The islands bear the name of John Marshall, the British explorer who sailed into them around 1788. But the Spanish navigator Alvaro de Saavedra was probably first to discover them around 1529. The Spanish sold them to the Germans in 1886 who lost them to the Japanese during the first World War. Finally the Japanese lost them to the American forces which landed there in 1944.

My father’s impression of the indigenous islanders

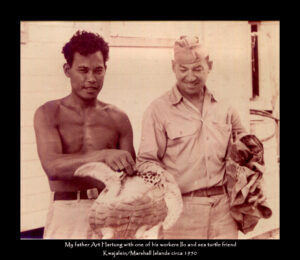

My father, a devout Catholic, saw the apparent goodness in these gentle happy people. He told me they had a spirit of kindness, innocence, and deep joy. Indeed he never failed to marvel at that.

The natives were unaffected by the obvious uneasiness and suspicion of the Marines. In fact they possessed a serenity, self-respect and assurance that seemed to be forces of insight which were integral with the forces of life, nature, the sea, and precious land. That gave them a kind of ancient wisdom in sharing their island paradise. My father noted their great skill in the natural ways of life. They had a trusting kindness and sense of well-being. These qualities were undoubtedly elaborated upon by the Catholicism of the Spanish, the Lutheranism of the Germans. Additionally they were likely rounded out by the Shinto and Buddhist influences of the Japanese.

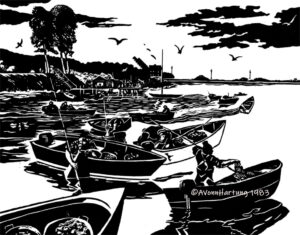

My father, a carpenter himself, found the men to be skilled in many disciplines. They were gifted navigators, fishermen and hunters. Additionally they were artists in the design and building of their modest homes and their outrigger canoes. These were double ended with triangular fiber woven sails that could simply be reversed to change direction when going or coming on the Trade Winds.

Both men and women were extremely gifted in the traditional arts of their ancestors. They made jewelry from the most beautiful of seashells and tortoiseshell implements of all kinds. That included delightfully beautiful heart-shaped feathered fans and all the domestic articles needed in the village.

Job safety became a top priority

The only art they found difficulty in mastering was the many electric and dangerous machines that they had to learn to run in the woodworking shops so essential to their work. Job safety became a top priority. To achieve this end my father spent a good deal of time and worry suffering along with them when they lost a finger or worse on the various electric saws and other equipment.

My father also learned, to his chagrin, of the skill and wisdom of the natives as sailors when he told me of the time when some of them did not report for work, following a sudden tropical storm. Worried, my father sailed to their island to enquire as to what had happened. Upon learning that they had never returned after their departure for work that day, he wanted to request a navy search party to look for them. This very much distressed the native elders, and he was given a lasting lesson in the seamanship of these fearless and gifted seafarers as they reappeared from the south several days later.

Thereafter he had a deep respect for their ancient ways and the strength and the integrity of their beliefs.

Conflicts between the Natives and the Merchant seamen

He also became aware of the propensity of some of the sailors for “re-routing” certain desirable government property to passing merchant seamen, in exchange for US dollars, which they would then use to cancel out gambling debts.

This problem came to a head when after an unannounced inventory of materials, certain items could not be accounted for. Later evidence was uncovered that the disappearance of the materials pointed to the Natives. It was left up to my father to solve the problem. He spoke to all his men together, and then spoke to both the enlisted sailors and the native workers separately. He was convinced that it was not any of his workers that were responsible. In fact the evidence pointing to the natives had been planted by the thieves. That brought the situation to a crucial point because then the natives were accused of the thefts. Consequently there ensued more harsh interrogations.

It was then that my father was able to show that the evidence had been planted to purposely throw suspicion on them, and that the stolen items could not have been taken by them, for their lack of physical capabilities, but rather that the theft had to have been orchestrated from the inside.

Investigation and Interrogations

The investigation and interrogations were broadened and, the officers in charge caught a sailor outside of the construction battalion in some lies. He ultimately confessed, whereby, the conspiracy was uncovered, and the guilty sailors punished.

Because my father had drawn a line in the sand to vouch for his men, he gained a deep respect from all involved, especially from the natives. From then on, the Natives spoke his rank of Chief with great reverence. And it was with reverence whenever my father spoke of them and flushed with warm memories of his time in the islands. There would come over him an ebullient joy as he related these memories. In fact he seemed to swing into a different rhythm of speech. It was a mixture of deep emotion, good humor, and childlike enthusiasm which we somehow understood as spiritual qualities that had been passed on to him.

My father’s adventurous stories

The stories that he related to us were not great adventures in the classical sense. In fact many were just sketches of everyday life, although some held an element of danger. For instance, the time he and a small band were cut off from their boats by a rising tide while in pursuit of fish along the reef. They just made it back across the rushing water up to their necks with sharks moving in.

All this was extremely exciting to us kids because of the exotic places, strange names and perhaps because of our own vivid imaginations that fit well into this seemingly tropical paradise.

My father, who neither smoked nor drank, preferred to spend his weekends, holidays, and time off with the natives on their islands, fishing, and hunting.

As the natives were not allowed to have firearms, they hunted wild pigs and goats in their traditional way, with traps and handheld weapons. They trapped seabirds with wire snares staked into the sand with small live fish placed on either side of the snare. They had a variety of nets but also dove freeform for octopus, lobster, giant clams and hunted sea turtle. At the end of a good weekend of fishing or hunting they would boil their spiced bounty with rice in a giant clamshell over an open firepit and share with the villagers, stories of the hunt.

A profound influence on my own life

These stories had a profound and lasting influence on my own life.

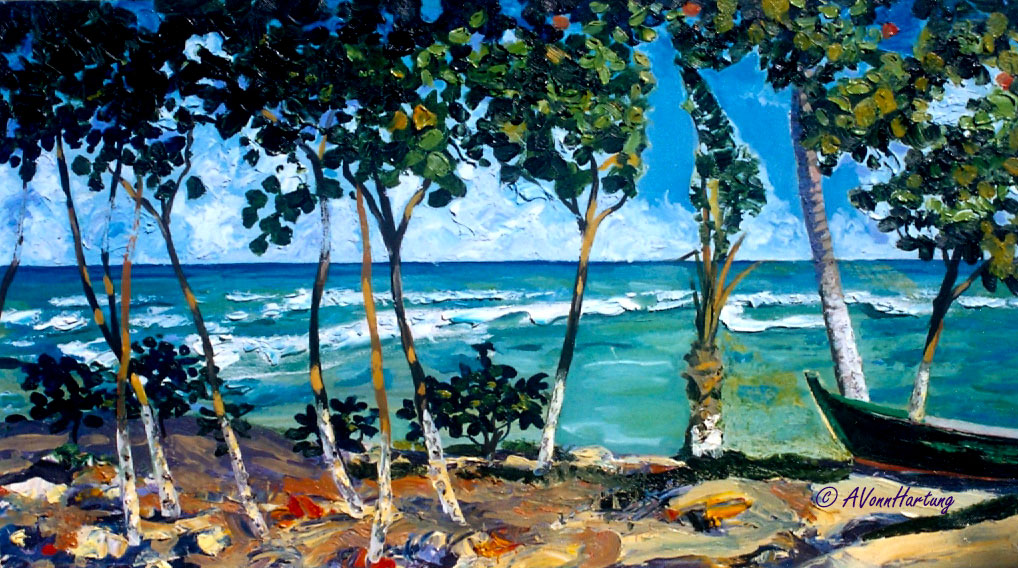

The images of dazzlingly beautiful settings of turquoise lagoons, blindingly white beaches cradling schools of outrageously colorful fish, and the natives together with their extended families sharing meals and companionship completed for me an idyllic picture of how life should be lived.

My father returns home from the islands

I remember the day when we expected my father to return home. We were whiling away the morning playing touch football in the vacant lot next to our house. Adjoining the lot in the upper half of a two-story house, lived Mrs. Butterfield, a good friend of my father’s younger sister Alicia. Little did we know that Alicia was visiting up there, watching us play and also awaiting my father’s return.

In the midst of our play, we saw something hit the ground. To our amazement, it was an empty beer can. It had a note sticking out of it. As we quickly huddled around to read the note, we all simultaneously raised our gaze skyward to follow the passenger plane which slowly made its way across the blue sky.

Incredible!!! Dad dropped us a note ! It read “About to land at Groton airport. Dad.” A moment I will never forget!

We ran, two teams in one crashing through the front door of our house to share the news with my mother. What happened after that is still a bit unclear. Belief meets disbelief. But I do remember my mother left sooner than later. We all cheered when she finally returned, pulling into our driveway with my father, smiling in his navy best. Aunt Alicia, head cheerleader.

A treasure trunk arrives!

It was about 3 months later when the first large trunk arrived. A footlocker full of the most treasure we had ever seen. Something right out of Treasure Island or the Arabian Nights! Layers upon layers of cowrie shell necklaces, palm and tortoise shell feathered fans, even grass skirts. Three trunks came in all.

They were gifts given to my father at a going away event before his departure from the island. During the celebration the villagers paid honor to him, each member placing before him a much-coveted gift, in gratitude of their friendship.

Being away from his dear wife Phyllis and us kids, brought his life and goals more clearly into focus. I don’t know if he ever kept in touch with his friends in the islands. A few letters were passed back and forth, but his life there faded into the remnants of the stories he told us and of the precious memories that he shared.

He continued to serve in the Navy reserves with small stints along the East coast and at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. Eventually he retired from both the Navy and his related job in the civil service. He continued to fish, lobster, clam, and scallop in and around his beloved estuary.

When he was young, he had four or five regular friends he went fishing with. In later years because of death or illness, the number sank to only one, his oldest and dearest friend George Cone.

And then ultimately, he fished alone.

Musings about my father’s glimpse of paradise

I believe in the islands my father glimpsed a bit of paradise. Indeed, he always seemed thereafter more spiritual, deliberate, and fulfilled.

If we have seen someplace uniquely beautiful and lived thereafter in its aura, if we have come upon a strange exotic place and absorbed some of its mystery into our soul, do we not also have to lose something? Give up something in return?

I ask this because I noticed in later years a kind of distance that came over him, perhaps even a sadness, sitting in his easy chair waiting for the long cold winters to thaw, waiting for Spring, waiting to fish again.

Was it in his distant look only the mesmerizing perspective of the years? Or was it something else, something more…

something he could see clearer now as he grew old…something distant but moving closer, just beyond the horizon…something he had known once before…where winter is only a shift in the Trade Winds, where fish school in the clear warm shallows, waiting to be taken,

where Spring is eternal, and youth is expressed in the promise of never having to fish alone…

A.Vonn Hartung

NOTE— I wrote this story originally for our family history that was written, compiled and published by my uncle Francis A. Breen circa 1995